Detection-tool: uncovering sensitive data¶

How the detection works¶

Our detection tool operates within the customer's perimeter, enabling it to utilize both the structure and values of the observed data when running the detection model. However, it's crucial to emphasize that when detection results are transmitted to Soveren's cloud, they do not include any actual data values; these are substituted with format-preserving placeholders.

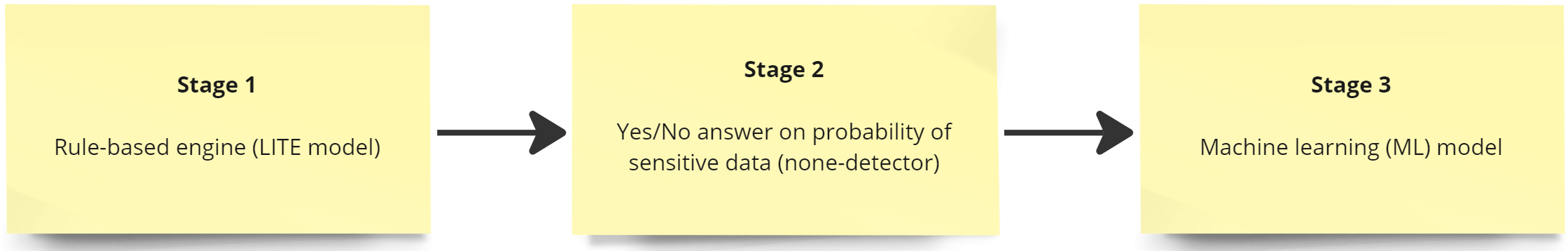

The detection tool employs a staged approach to detection.

In the first stage, we run the rule-based engine that we call the LITE model. This includes matching based on regular expressions, as well as functions that operate on top of one or several detections to check complex rules which cannot be reduced to simple or efficient regex patterns. The LITE model is optimized for precision.

Secondly, we run a classifier that examines the entire payload to determine if there's a non-zero probability that the payload could contain sensitive data. We refer to this as the none-detector. If the answer is yes, then the ML (Machine Learning) model is run as the third step. This third stage consumes considerably more resources than the previous two stages.

Before running any stage, we trim very large payloads to a sensible size. For example, for JSON payloads, arrays are reduced to the first ten elements, and the number of keys is trimmed to a certain (large) number. If the payload is indeed large, then only the LITE model is employed.

This approach allows us to balance the load versus detection quality, in terms of both coverage and precision/recall.

Currently, the detection is designed to support structured data formats such as JSON, YAML, and CSV.

Dataset and training¶

How the dataset is constructed¶

The primary challenge in building our detection model was the need to identify sensitive information, such as personal data, which people are often unwilling or legally restricted from sharing.

We address this challenge by generating synthetic data that mimics real-world scenarios.

To bootstrap the learning process, we have collected JSON schemas and examples from legally accessible, publicly available sources, such as APIs on Github from various projects. We've marked those schemas with data types using our own judgment and different models, particularly BERT. Currently, we also use GPT, which was not available at the time of bootstrapping with a sufficient performance level. We then created a series of examples populated with synthetic values, utilizing our custom-built generators, which often incorporate dictionary-based methods.

Additionally, we gather example structured data schemas (such as JSON schemas) from our customers. These schemas are utilized in a manner similar to our initial bootstrapping: populating them with synthetic data from our custom-built generators.

We periodically seek new data sources to enrich our dataset, which continually grows with each new customer as the model improves with every additional schema available.

To summarize, our dataset is derived from two major conceptual sources:

-

Legally available public sources

-

Structured data schemas from our customers, such as JSON schemas

How we measure quality¶

Our dataset is divided into two parts: training and holdout. We use the former for model training, and the latter is used for consistency and quality evaluation between model versions retrained on an updated training dataset. Cross-validation is employed during training.

When we receive detection results from our customers, we conduct spot testing for false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN). We can conduct these checks efficiently because, although the actual values are not accessible to us, format-preserving placeholders are used. Utilizing these placeholders, along with information about the data's structure and composition, enables us to apply various heuristics to infer data types with a high degree of confidence. Additionally, we carry out pseudo-random manual checks, which are guided by the historical frequency of detected FPs and FNs associated with specific data types.

In addition to monitoring model quality on the holdout dataset, we use the results of the spot checks to assess quality in production. Our primary quality metric is Fß, with ß set to 0.5, to prioritize precision over recall.

Model training and improvements¶

Periodically, we seek openly available data to enhance our model and synthetic data generators. Such acquisitions always lead to a major update of the model, significantly impacting both the training and holdout datasets, as well as the learning process's hyperparameters.

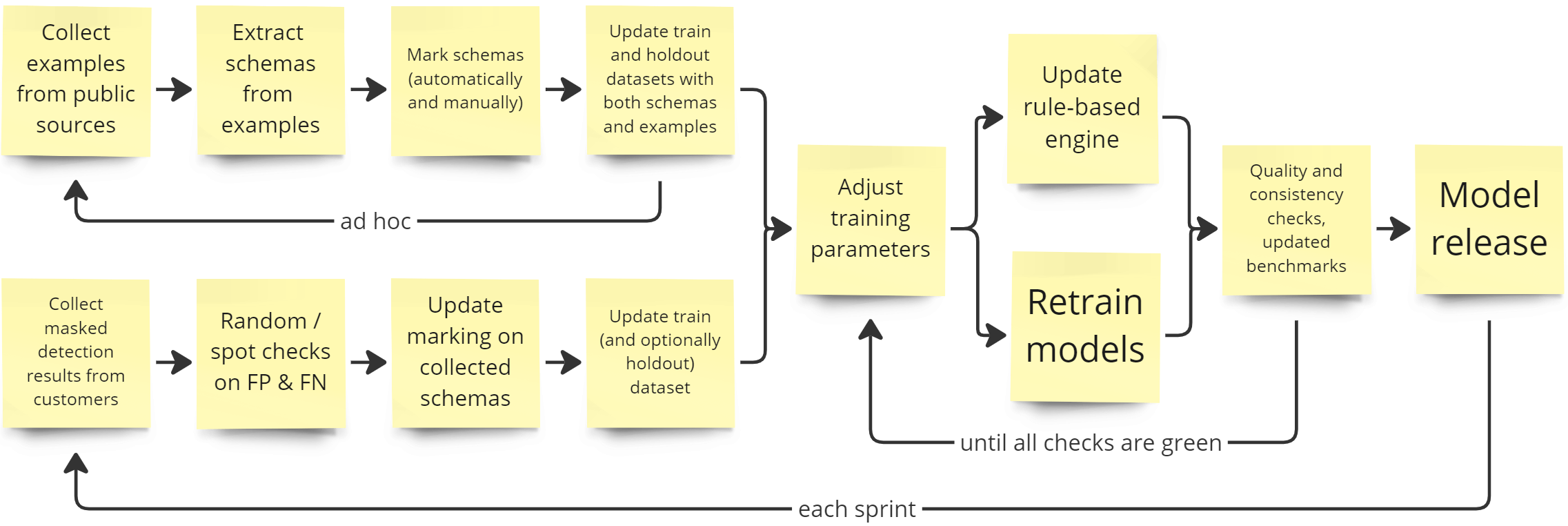

Furthermore, we regularly utilize structured schema samples observed in our customers' environments for continual model improvements. We have established a process that ideally results in an updated model version with enhanced quality at the end of each sprint.

The primary steps in this regular refinement process include the false positive/false negative (FP/FN) checks previously mentioned, labeling of schemas through both automated and manual methods similar to our initial dataset bootstrapping, updating the training dataset, and subsequently retraining the model.

Following the retraining, we evaluate its quality against the established baseline. Should this assessment indicate an improvement, we proceed to release a new version of the model.

Over-the-air (OtA) updates¶

In several cases, the detection tool can be updated with new model versions without redeployment. This applies when there are no changes to the core model structure, including new data types, or its accompanying logic. Essentially, the updates are confined to modifications of weights and rules.

Periodically, the detection tool checks with the Soveren cloud to determine if any new model versions are available. If new versions are found, they are downloaded and become immediately operational. We refer to this process as the over-the-air (OtA) update.

Adding new data types¶

Currently, the process of introducing new data types to the model is not automated. This requires manual incorporation of the new types into all models, construction of necessary synthetic generators, updates to the training and holdout datasets, and subsequent retraining of the models.

If an updated model version incorporates a new data type, it cannot be updated via over-the-air (OtA) methods.